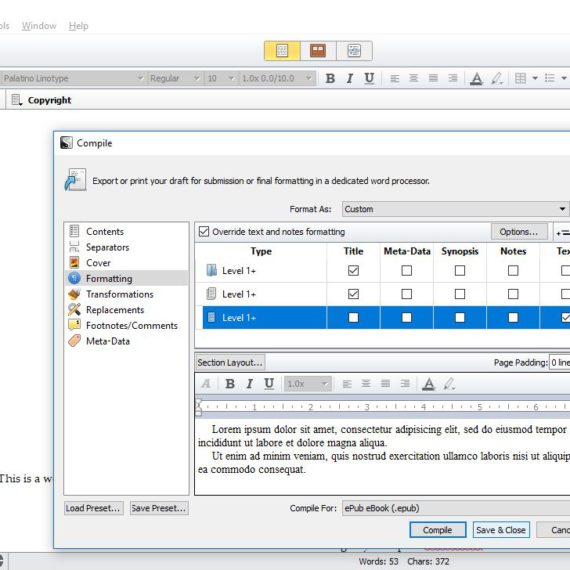

Here’s an excerpt from CLEARCUT, the first novel in the Adrian Cervantes series.

Excerpt also available in PDF.

PROLOGUE

They were told to take care of the old man, but they weren’t told how, so they decided to have a little fun first.

There were three of them: Payden, the oldest at twenty-six, the acknowledged ringleader, slow to act but definitive; and the two Blaylock boys, Jimmy and Tommy, twenty-two and twenty, given to messing with each other if left untended, like a cigarette butt in a pile of dry leaves.

Even while they were waiting, in the muddy turnout across the lane from the roadhouse, they started fidgeting in the back seat of Payden’s truck. Jimmy accused Tommy of farting. Payden ignored it as long as he could until the squabbling turned to actual violence—the echoless smack of meat on bone, Tommy’s plaintive whine as he fought back—and he had to do something.

“Quit it,” he said. He had one of those deep, tired backwoods voices, the vowels hanging together. The Blaylock boys laid off.

About ten minutes later a rhombus of light cut across the roadhouse’s woodchip lot. A burst of classic rock followed it. Heavy footsteps chuffed across the chips: an irregular stride, weight shifting between worn Carhartt boots. Payden’s vantage point was narrow, just a gap between the thick pine trees at the end of the driveway, but it sounded like the old man. He raised a hand to get the Blaylocks’ attention, quieting them, forestalling a discussion over who’d stayed hot after they graduated that was about to turn into another fight.

It was the old man. He was walking heavily but not staggering. More tired than drunk, Payden guessed. A woman closer to Payden’s age trotted out after him. She caught the old man while he leaned against the doorframe of his Tacoma, one hand on his elbow.

He shrugged her off. Not angry, but weary. Payden, who’d spent two hours in a cramped Ford cab with the Blaylock brothers, almost sympathized. Then he blinked and shook his head, as if cleaning the emotion off the slate of his mind. Sympathy wouldn’t help.

The woman backed away, saying something else. The old man didn’t respond. Her body language cycled from hope, to reluctance, to defeat: hands dropping to her sides, shoulders slumping, turning her back to him as she walked back inside. The old man unlocked his truck and climbed in. In the pale glow of the dome light, Payden saw the old man slump back against the headrest. Sleeping another one off in the parking lot, he thought.

“Here we go,” Payden said.

The three of them got out of Payden’s truck, closing the doors softly at his direction. They crossed the tree-lined road. The night was thick with the smell of damp loam and sharp pine. Payden glanced back once, at the Blaylocks, but they were quiet and kept their hands to themselves. They might have been fuck-ups in every other aspect of their lives, but they could be relied on to follow a leader’s example.

Payden patted the heavy lump in his jacket pocket to keep it from swinging with his stride.

They approached the old man’s truck. Payden waved the Blaylocks around to the driver’s side. When they were in position, Payden opened the side door, pulled himself up via a meaty grip on the cabin roof, and slid into the front passenger seat. He shut the door quietly behind him.

The old man blinked out of his unconscious stupor. He stared at Payden, uncomprehending. Payden had been rehearsing this bit in his head—he had an opening line he was happy with—but for the moment he stared back. For the Blaylocks, the violence was the fun part. But for Payden, it was having someone in his power: that moment they surrendered, acknowledging that they no longer had a say in what was coming. Sometimes they begged, which was always nice.

The old man spoiled it. “The hell you doing …” He trailed off, wiping some spittle off his beard.

The dome light clicked off.

Well, let’s see how that opening line works, Payden thought. “You promised to give us a ride! Remember?”

The old man blinked, processing “us” for a second. He took in the Blaylocks, standing just outside his door. He said nothing, but his breathing grew shallower and quicker.

“Remember?” Payden’s plan didn’t hinge on the old man swallowing this line, but he wanted to try it out. He thought it was clever. “They’re closing up? Kicked us out? I told you we could go drink at my cousin’s cabin, maybe smoke a little. Just need you to give us a ride, is all.”

The old man’s soft chest rose and fell, a pulsing little flannel lump. He looked at Payden’s hands. “I haven’t said anything.”

Payden glanced toward the roadhouse. The old man’s truck faced the front corner. The nearer wall didn’t have any windows. Whoever was inside might see the truck if they went to the front door and stared at an oblique angle through the glass panel in the front, or if they opened the door all the way and poked their head out. But they’d be cleaning up now. Payden could hear the bass of the stereo echoing around the empty interior. The dishwasher would be running and mop water would be sloshing across the floor. They’d have bigger things to worry about than a regular sleeping one off.

“Keys,” Payden said.

The old man didn’t move. “I haven’t said anything.”

“That’s not what I fucking asked you.” He shoved the old man’s arm aside and fished in the pocket of his denim jacket. He took the keys out. He reached across the old man like he was some mute obstruction—a coat thrown over the seat, perhaps—and opened his door. Jimmy caught it and opened it the rest of the way.

Payden got out on his side and dragged the old man across the front bench so Jimmy could get in. The old man didn’t even put up a token fight. Payden watched him—his head limp, staring at his hands curled up in his lap—while Tommy came around and got in the passenger seat. The Blaylocks sandwiched the old man in the front.

“The switchback. Like we talked about.” Payden shut the door. Jimmy peeled out while Payden was still crossing the road. His heavy jacket pocket knocked against his hip bone while he jogged.

Payden got in his truck and followed the Blaylocks as they drove the old man down the road, down the winding tree-lined path that took them out of the hills. Having the Blaylocks out of his truck wasn’t the relief he thought it’d be. It was too quiet. Payden didn’t mind the quiet, but he needed something to set it against. He needed those two morons’ aimless squabbling to be quiet alongside, to be superior to.

They emerged from the trees, with the wall of the hill on one side and the few streetlights of Cullinan in the valley below. Payden wondered who else might be up at this hour. Other drunks like the old man, perhaps, and the businesses that served and cleaned up after them. Maybe one of the sheriff’s boys, circuiting the six-block downtown in his rattling cruiser. But Cullinan didn’t have much of a nightlife. Not that Payden worried about witnesses. He just liked moving around when no one else was.

Ahead, the old man’s truck jinked sharp, left to right. Brake lights flared. The truck pulled onto the shoulder, overlooking the valley.

Payden didn’t swear. Why disturb the quiet with cursing that no one else could hear? Instead, he pulled onto the shoulder about thirty yards behind the old man’s truck. He got out and approached on foot. He pressed one fist against the heavy jacket pocket on his right side.

Jimmy got out while Payden was still approaching. He looked down at himself, preoccupied with wiping something off his jacket. He didn’t seem to realize Payden was approaching until Payden drew within a foot, and even then he didn’t look up. “Son of a bitch,” he murmured.

Payden grabbed Jimmy’s shoulder. Jimmy stopped. Payden angled him forward. “The switchback.”

“I know, Payden, but son of a bitch got sick.” The epithet was slurred, its edges worn off from frequent use: suvvabitch.

“And you had to stop to clean up.”

“It’s all over my fuckin—” Jimmy looked down at his jacket. He let his hands flop to his sides.

“Because you wanted to look good? It’s important for something like this that you look good?”

The truck rocked on its springs. From the darkened truck cabin came a violent motion and the sound of a fist smacking flesh.

Swearing, Payden opened the driver’s door. Tommy wailed on the old man, brushing his arms aside with one hand and punching him sloppily with the other. The old man grunted, trying to stretch back and cocoon up at the same time. The result would’ve been comical, even to Payden, if it hadn’t been a complete waste of time.

Payden tried to reach past the old man to push Tommy off, but there wasn’t enough room in the cabin. The old man flailed, pushing Payden away, as if fearing assault from both flanks. Growling in frustration, Payden got out, jogged around the hood, and opened the door on Tommy’s side. He dragged Tommy out by the belt, tossing him to the muddy shoulder.

Tommy skidded back until he hit the crooked guardrail. He pressed himself against it to help himself up. He glared at Payden. “He got sick on me. All over my pants. Some of it got in my—”

Payden crossed the distance between them in two strides. The second stride turned into a right cross: foot planted, shoulder twitched forward, marble fist into porcelain jaw. It wasn’t a beatdown out of anger, as Tommy’s had been, though Payden was plenty angry. It was discipline.

Tommy’s knees buckled, pointing outward, and he slumped to the mud.

Payden went back to the truck. The old man propped himself up on his elbows and touched his face. He winced as he made contact with his busted lip, his reddened cheekbones. The numbness from his earlier drunk must have worn off.

Payden climbed into the cabin. “Hell.” He took a handkerchief from his back pocket and wiped the blood off the old man’s mouth. “How you feeling?”

The old man’s jaw shook as Payden pulled his hand away. “I haven’t told anyone. I won’t tell anyone.”

Payden nodded. “How’s the jaw? Go like this; does it click or anything?” He opened and closed his mouth like a nutcracker.

“Please.” The old man’s shoulders heaved. “Just … just let me …”

And that was what summoned Payden’s anger back: the sheer stupidity of that plea. Just let you what? Let you keep drinking yourself to death? Let you keep whining to anyone who’ll listen about how you caught a bad rap? What do you have to live for, anyway?

He reached back for his laden jacket pocket. “I’ve got something for you.”

“Payden, no.”

Payden pulled out a fifth of vodka. He unscrewed the cap with one hand. The other hand pulled the old man closer, sliding him across the vinyl bench.

“I haven’t told anyone. I’ll never t—”

With one massive hand, Payden pinched the old man’s nose shut and forced his head back. He forced the bottle between the man’s teeth and tipped it. The sharp varnish smell of cheap spirits filled the cabin. Payden tucked his chin to keep the old man’s flailing from scratching up his face.

The old man started sputtering and choking. Payden kept pouring. Much of the glugging vodka seeped down the old man’s jaw, soaking his shirt.

When the bottle was empty, Payden let go of the old man’s nose. The old man sat on the bench, arms limp at his sides, gasping for air. Payden got out and went to the guardrail, wiping the bottle down as he went. He flung it into the darkness and waited until he heard it land in some underbrush.

He went back around the front of the truck, nearer the road, where Jimmy was helping Tommy walk off that right cross. Jimmy looked up at Payden. His eyes were blank: not scared, not angry, not even questioning what had happened—just a pair of big empty saucers, waiting for Payden’s instructions to fill them.

“Go get your truck from the switchback,” Payden said.

“That’s like …” Jimmy turned, staring into the unlit distance, as if he might see a sign. “… like, two miles from here.”

Payden ignored the interruption. “Stay on the shoulder. If you see headlights, hit the deck. No one can see you out here, remember?”

Without waiting for further objections, Payden clambered back into the driver’s side. The old man hadn’t moved. His breathing had slowed a great deal, like a child about to fall asleep. But he wasn’t out yet. His head turned on his limp neck, and his watery gaze rested on Payden. His lips moved weakly, pulling back from the teeth. “D …” Flooded with cheap vodka and stinking of fear, he lacked the strength to finish. But Payden might have guessed what he was trying to say.

Don’t.

Payden put one hand on the old man’s jaw, the other on the crown of his head. He tilted the chin up, resting the head perpendicular to the spine. Then he took a deep breath and twisted sharply.

The crick-ack reverberated through the cabin.

Payden used his handkerchief to wipe down the steering wheel, console, and bench. He got the door handles, the door levers, and the little calf tongue that adjusted the rearview mirror. When he was satisfied, he pulled on the kitchen gloves he’d tucked inside his jacket earlier in the evening.

There was a narrow gap between the guardrails at the edge of the shoulder. A man would have to turn sideways and shimmy to get through it, and it would lead to nothing but a forty-degree decline and a long tumble through the underbrush. But it was wide enough that a man might stagger up to it and piss if he pulled over.

Payden slung the old man over his shoulder like a sack of laundry. He carried him to the gap in the guardrail. With one grunting heave—bend at the knees, deep breath, explode upward—he tossed the old man down the hill. There were a few moments of splintering branches and dislodged pine needles. Then silence.

Sighing, Payden turned and headed back to his own truck. He left the old man’s vehicle in the darkness behind him, the door open, the door alarm chiming into the night. He trudged uphill, feeling it in his calves, the adrenaline and anticipation wearing off. As much as he hated to admit it, the whole improvisation had stemmed from trying to have a little fun with the old man first. Next time—and Payden didn’t kid himself there wouldn’t be a next time—he’d dispense with the frivolities.

one

Everything Adrian Cervantes knew about the town of Cullinan came from a dead man’s reminiscences and two hours of online research. The research he had done on the plane, scrolling through his phone as the mist parted over Sea-Tac. The town’s cheery website sold Cullinan as a tourist destination, perfect for fishing, hiking, camping, and other wilderness pursuits. There were news articles about the town locked behind paywalls; the snippets alluded to industry in decline, bankruptcy, exodus. The dead man had alluded to the same, albeit more colorfully.

Go up in the hills at night and try to score, man. Or just park on the overlook and chuck beer bottles into the woods. That’s it. No colleges, no shopping malls. Nearest movie theater was in Aberdeen. Just a lot of pasty white boys getting doughy like donuts. Wasn’t all gang violence and quinceañeras like your hometown, eh, Barrio?

Sure, Prep.

Even now, seven years on, driving alone in a rented SUV from Sea-Tac to Cullinan, Adrian could hear Ricky Quinones giggling at his own jokes. They had bonded early in their deployment. Two Chicanos on the same squad—look out everybody, count your hubcaps. From Ricky’s stories, Adrian expected a cookie-cutter Pacific Northwest suburb: quarter-acre lawns, rustic-style houses with vinyl siding colored to look like timber. He expected a bucolic place where a kid would have to work to get in trouble, get sent off to a military academy, get a taste for the dirt and metal and enlist after graduating, like Ricky had.

As Adrian passed through Cullinan’s downtown, however, he started seeing the marks the exodus had left. Brick storefronts with LIQUIDATION or GOING OUT OF BUSINESS signs flanked him as he drove. People waited for buses or sat on benches in lazy conversation; no pressing business called them elsewhere. It was the slow, unambitious pace of a town without industry. Even for a Sunday afternoon, it felt dead.

The GPS steered Adrian into a residential development, laid out in a green valley wet with recent rain. Each house had a small lot of dewy grass to itself. Maybe one in five houses had boards on the windows, or an official notice in glistening laminate tacked to the door. Of the houses that still looked occupied, many had neglected yards: grass run wild, cars on blocks out front. It was a sunny day—or would’ve been, behind the overcast—but Adrian saw no children riding bikes or chasing balls, no young couples walking dogs or pushing strollers.

The lack of kids was what made Adrian’s breath come high and shallow. Rolling through Mosul, one passed a thousand different things on the road that could signify an ambush or IED: an unusual piece of refuse, a stack of crates, an abandoned vehicle. A street without kids was a dead giveaway. Adrian idled at a stop sign for a minute until the spots cleared from his vision, until he reminded himself that whatever else might threaten him in Cullinan, it wouldn’t be an ambush.

Adrian reached his destination after a few more turns down suburban blocks. The GPS warned him it was coming up on the right, but the line of cars called attention to it first. Adrian cruised by slowly, trying to scope out details. People lingered on the front lawn, nursing cigarettes or red plastic cups. They were all dressed somewhat formally, in comfortable blazers or light dresses in muted colors. They glanced up as Adrian passed.

He pulled over at the end of the block. Shit. In his ideal scenario, he would be paying this call alone. He thought for a moment, drumming his fingers on the steering wheel. Come back later? Tomorrow? But the gathering was already too much of a variable. Who knew what another twenty-four hours of delay might bring? Mr. and Mrs. Quinones might be gone by then.

Adrian examined his outfit in the visor mirror. He wore one of his favored designer suits, charcoal gray with a silver pocket square. He’d found this sort of outfit put strangers at ease; today, joining a party in progress, it was just a happy coincidence. Donning a high-end suit also put Adrian in the right frame of mind, the same way tightening the straps on his tac vest had. If he was going to carry one point six million dollars in his pocket, he had to look the part.

The house looked well kept: lawn a bit overgrown, but all the siding intact and the windows clear. The interior was dark from all the people packed inside. Adrian threaded between a clump of older men on the porch—retired mill workers, most likely, with craggy faces and muscled forearms. Conversations faded to silence as he approached. Adrian nodded a greeting.

“You get yours early?” The speaker was an older man, face lined like a fist.

“Beg your pardon?” said Adrian.

“Couldn’t wait to get y’self a new suit. New ride.” The older man’s fingers ran up and down his own corduroy jacket, as if in mocking comparison. “You work your whole life, and—”

“Dad, he’s not from the mill.” The man sitting next to him, roughly Adrian’s age, put a hand on his arm.

The older man turned, squinting. Adrian took advantage of the confusion to smile and wave to the others and press on. Wonder what that was about, he thought.

A dozen pairs of eyes turned to Adrian as he entered, and most lingered for a moment longer than normal. Perhaps the suit had been a mistake; he was the best-dressed man in the room by at least two thousand dollars. The other men wore denim jackets over church clothes, or old suits that no longer covered the wrists and ankles. They were locals, Adrian the outlier.

An older woman approached Adrian. Mrs. Quinones, he thought, but she didn’t match the photo on his phone. She appeared roughly the same age, though. Neighbor, perhaps.

“There’s a guest book if you didn’t get a chance to sign at the service.” She gestured to a massive white tome on an end table. “How do you know the Quinoneses?”

Adrian nodded as she steered him toward the guest book, his heart already sinking. He’d been denying the obvious since he first noted the guests’ formal attire and subdued tones. He couldn’t pretend this wasn’t a memorial service any longer. Disengage; regroup; try again later. But he was already in the door. He’d already made an impression on a small crowd. Better to stay in, hand over the money, and make an awkward exit.

The woman hovered by Adrian’s elbow, eyes wide in that Yes? posture. He realized she wouldn’t leave him be without an answer. “I served with their boy, Ricky.”

Her hand fluttered to her mouth. “My goodness. Oh, I have to tell Marie you’re here.”

“Ma’am, you don’t—” But she was already zipping off toward the back of the house. Christ. The last thing he wanted was an audience for the handoff—a crowd hovering, Thank you for your service, unwilling to leave him be until they’d been satiated with war stories and empty aphorisms. He broke line of sight by slipping into the living room, a short left off the main hall. People stood in twos or threes by the windows, or sat on the couch before a spread of store-bought sandwiches. A gray slate fireplace stood set into the far wall. On the mantelpiece, flanking a candle of the Virgin, were two framed photos.

The photo on the left was of an older man. He had a thick black mustache over a brilliant smile that burst from the frame. He was dressed in a garish suit jacket—red and gold plaid—over a reindeer sweater. His left hand, holding a red plastic cup, was tilted toward the camera as if in greeting. His right hand beckoned the viewer: Come on, join us!

Adrian had never met the man, but he felt he recognized him already. He was everyone’s favorite uncle, ready with a corny joke or a classic song. Life seemed to bubble out of him like a drink overflowing. Eric Quinones.

On the right side of the candle was a photo of a much younger man, no more than twenty. He wore Class A dress blues, with a beret folded just so. His nameplate, R. QUINONES, was just visible above the bottom edge of the frame. Between his unlined face and his formal mien, one might think he had never smiled in his life. Adrian had never seen Ricky looking so serious.

Hey, Prep.

Hey, Barrio.

Adrian looked away, picking at the corners of his eyes. Through the other end of the living room, he saw the kitchen, and the sliding glass door that led to the back deck. A woman sat there, dressed all in black, staring down into the cup of coffee nestled in her lap. Men in mourning clothes flanked her like bodyguards. She had the same serious brow as the young man in the photo.

As Adrian watched, his greeter bustled up to the woman in black and bent over to whisper something in her ear. The woman in black looked around, one hand over her heart.

His face burning, Adrian snuck from the living room, back the way he’d come. Off the main hall, opposite the living room and well away from the back deck, lay a dining room. The chairs had been pushed to the corners, and two massive coffee urns dominated the table. Adrian poured himself a cup.

“Finding everything okay?”

Adrian turned. The speaker was about six four and maybe twice Adrian’s mass, a vault door of a man who looked ten years his elder. He wore an insincere smile that made Adrian’s heels twitch.

Adrian held up his cup. “Everything but the milk.”

“Noticed you got lost between the living room and here.” The man stuck a hand out. “Cam Slade, Thurston County deputy.”

Law enforcement. There was the slightest hesitation as Adrian returned the handshake. “Adrian Cervantes.”

“You know the family, Mr. Cervantes?”

Adrian gave a noncommittal grunt as he sipped his coffee. “They’ve been through a lot, I take it.”

“Yeah. First Ricky, now old Eric.” The deputy rubbed the back of his neck and glanced toward the living room, where the impromptu shrine had pride of place. “Marie—Mrs. Quinones—left on her own.”

“Are there any concerns about …” Adrian gestured vaguely, hoping Slade might fill in some details unprompted. Her health? Her finances? Her stability?

Instead, Slade sucked air in through his teeth. “That’s a subject you might want to drop. Friendly word of caution.”

“Understood.” That was all the cue Adrian needed to exit. His plans for a quick visit and a quicker handoff vanished. But the deputy seemed comfortable in the doorway, blocking Adrian’s path.

“And where do you come from, Mr. Cervantes?”

“Drove up from Sea-Tac early this morning.” Adrian gestured toward the lawn, and the neighborhood outside. “Quite a line of cars out front. It’s good to see people coming together, in a time like this.”

“Yeah. Good turnout. I think people recognize that Marie needs support. Or, at least, they’re not going to hold the past against her, now that Eric’s gone.”

Adrian took another sip to mask his confusion. Hold the past against her? But before he could follow up, someone called the deputy’s name from across the room. The deputy smiled, clapped Adrian on the arm hard enough to rattle his teeth, and sauntered off.

His path now clear, Adrian headed to the kitchen to throw out his coffee. He glanced out the window as he did, still curious about Mrs. Quinones. The entourage flanking her had scattered: some at the end of the driveway, speaking to a caterer; some murmuring over cigarettes. She was less than ten feet away.

Just hand her the envelope. It would be a new cruelty in its own right, bringing up a mourning wife’s dead son and dropping a million-six in her lap without follow-up. But it minimized Adrian’s exposure and it got the job done. It was a risk worth taking.

The widow didn’t look up until Adrian was directly before her, crouching to meet her gaze. “Mrs. Quinones?”

Her eyes were wet and red, her head tilted with confusion. She looked as if she had been confused for several days and never expected to stop. She said nothing.

“My name is Adrian Cervantes. I’m terribly sorry for your loss, Mrs. Quinones.”

She nodded, but there was no warmth or acknowledgment behind it. It was a mechanical gesture: a civil reflex, but no more.

“I’m also sorry for Ricky, ma’am. I knew him, from—”

“From overseas?” This lit a spark. She set her mug down on the stained deck bench and took Adrian’s hands in hers.

“Yes, ma’am. We served together in the 75th.” He sat on the bench next to her. Already the plan to make this quick had fallen apart. But the lonely desperation in Mrs. Quinones’s eyes snared him, tripped him, made it impossible to walk away. “He was a good soldier. Everyone liked him.”

Hey, Barrio.

Hey, Prep.

“Were you there? When …” Mrs. Quinones trailed off, her lower lip shaking.

A man about Mrs. Quinones’s age—tall, thinning blond hair, not quite as big as Deputy Slade but near to it—hovered near the sliding door, glaring at Adrian. He seemed torn by the need to give the grieving widow privacy and the desire to bounce Adrian like a rowdy drunk. Adrian shifted on the bench, keeping his weight on his feet. May need to move soon.

“This is actually about Ricky,” he said. “About you and your family, rather. There’s something …”

Adrian sighed, fumbling inside his suit jacket. He had rehearsed this speech on the flight in, lips moving silently as he tried the words out again and again. But nothing on the ground was as he’d envisioned it.

He took out the envelope in his pocket. It trembled in his hands. “Mrs. Quinones, there’s this … there’s a sum of money that should go to your family. To you, I suppose. Ricky would—”

Then he cut himself off. The word money had quickened Mrs. Quinones’s breathing. She pulled her hands back as if from a snapping dog.

“He didn’t!” She shook her head, pressing her fists to her mouth. “He swore he didn’t! He swore he wasn’t involved!”

Adrian stared at her, slack-jawed. He had no idea what this meant. He tried to take her hands, but she flailed at him. Withdrawing, trying to make himself look harmless, he stood up and backed away.

Footsteps pounded across the deck. The older man, with the blond hair and big shoulders, vaulted to within a handsbreadth. “The hell did you do?”

It shouldn’t have gone down like this. “I was just talking to her.”

“What’s that in your hand there?” The older man reached for the envelope. Adrian twisted away, slipping the envelope into a side pocket. He put a hand on the older man’s chest to check him.

The man slapped it away. The smack of flesh on flesh turned every head.

Time to go. Adrian clattered down the porch steps, his eyes lowered. He ignored the older man yelling, ignored the murmurs surfacing around him. He’d had a chance to make a graceful exit, to revise his approach, and he’d blown it. He had experience silencing fear and doubt and recrimination while he focused on the task at hand, but that didn’t make this pleasant.

“Tommy!”

At the head of the driveway, a kid—late teens, early twenties, his button-down shirt rolled up to his elbows—looked up from his cigarette as the old man called out. He interposed himself in Adrian’s path. “Why’nt you slow down, hmm? Mr. Casselman wants a word with you.”

“Sorry.” Adrian tried to cut around him.

The kid shuffled to stay in his way. “You will be sorry; that’s a promise.”

Adrian sighed, fighting down a surge of impatience. He stepped outside himself for a moment. The kid was an obstacle, sure, and came off like a bit of a prick. But Adrian was the stranger here. He had to play this carefully to keep from salting the earth any further.

So Adrian took a step back, then another quick step on the diagonal. The kid, Tommy, saw it coming and reached out to shove Adrian’s shoulder. But Adrian dipped his shoulder, just enough for the boy’s calloused palm to graze over the linen. The kid staggered forward until Adrian’s shoulder nestled in his armpit. Then Adrian shrugged, hard.

It worked a little too well. The kid stumbled to one side, having committed too much weight to the shove. He clipped his boot heel on the retaining wall. Wheeling his arms, he toppled into the garden, crashing into a low shrub.

A hand clamped on Adrian’s elbow from behind. He tried to spin free, but another hand locked on his opposite wrist, preventing him from turning. In the second it took him to realize he shouldn’t fight, Deputy Slade finished binding him up, cranking Adrian’s hand up between his shoulder blades and shoving him forward.

The deputy spread-eagled Adrian against the hood of the catering van and patted him down. The usual litany of questions—”Any weapons on you? Anything that might stick me?”—echoed off numb ears. Adrian looked back toward the porch, where Mrs. Quinones stood at the railing. She watched him with the most condemnatory anger he’d ever seen in another human being: a willingness to kill, to not just take someone’s life but erase them from ever having existed. That Adrian could bring that out in another person, on the day of her husband’s funeral, scared him more than he could say.

# # #

If you enjoyed this excerpt of Clearcut, you can continue reading the rest on your Kindle or in paperback.

Visit the order page for Clearcut to buy it today!

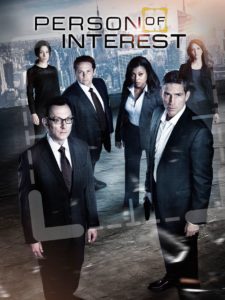

Two of my favorite TV series of the past 10 years – shows that I keep coming back to – are Burn Notice and Person of Interest. As formula shows, they work: a retired spy with exceptional skills helps innocent people solve problems that the cops can’t help with. They have a variety of contacts and allies – some intimate, some reluctant – who help them on their way. They’ve done bad things in their past, but their freelance vigilantism gives them a chance at redemption.

Two of my favorite TV series of the past 10 years – shows that I keep coming back to – are Burn Notice and Person of Interest. As formula shows, they work: a retired spy with exceptional skills helps innocent people solve problems that the cops can’t help with. They have a variety of contacts and allies – some intimate, some reluctant – who help them on their way. They’ve done bad things in their past, but their freelance vigilantism gives them a chance at redemption.